Michael’s Story: Surviving Eastwood Park

Content Warning: This story contains vivid accounts of physical and emotional abuse, racism, and institutional cruelty that may distress readers. For support, contact Samaritans at 116 123 or visit www.samaritans.org.

Summer 1981: A Reckless Dare

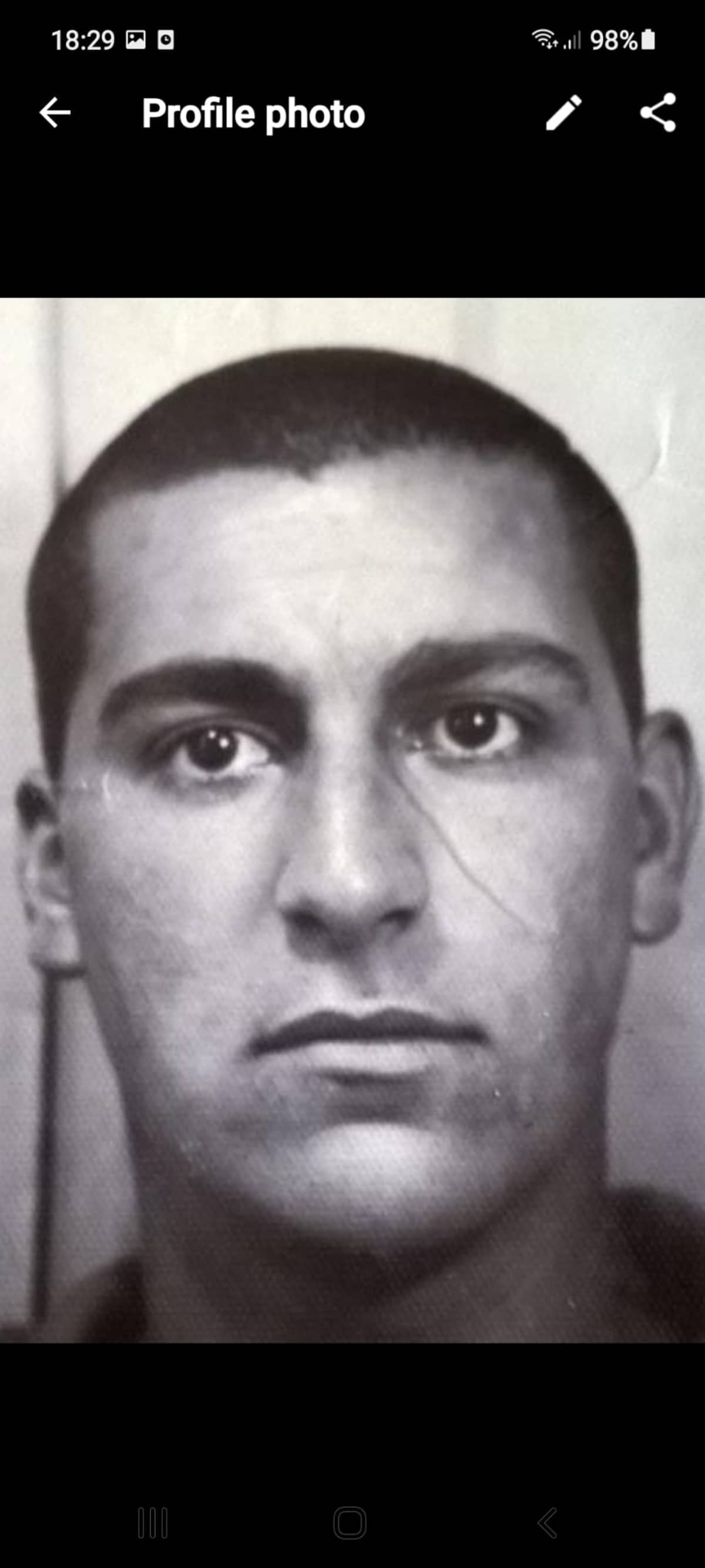

It’s 7 July 1981, and the Birmingham sun bakes the cracked pavement outside a police van where you, Michael, sit handcuffed. You’re 15, a wiry kid who loves The Clash’s rebellious chords, your pulse hammering like their drums. Sweat beads on your forehead, sticking your dark hair to your skin. Born to a Yemeni father and British mother, your brown eyes flicker with defiance, but fear knots your stomach as the van lurches toward Eastwood Park Detention Centre in South Gloucestershire. A stupid dare—flicking a match through the letterbox of Dean’s furniture shop in Halesowen—has branded you an arsonist, charged with handling stolen goods. After four months in Farehaven children’s home, where psychiatrists scribbled reports urging confinement until you’re 18, the judge opted for Margaret Thatcher’s “short, sharp shock” policy: three months in a place designed to break boys like you. Eastwood Park’s iron gates loom like jaws, and you sense the cruelty waiting inside. The 1970s offer staff unchecked power, which they wield with a sadist’s glee.

Arrival at Eastwood Park

You step into Eastwood Park, and the air chokes you—bleach burns your nostrils, sweat sours the damp concrete, and despair clings like mildew. Officers’ boots echo like gunshots, their barked orders drowning out the stifled sobs of boys aged 14 to 17. This isn’t reform; it’s a machine to crush spirits. Your cell is a tomb: a thin mattress sags on a rusted frame, a barred window leaks grey light, and walls bear the scratched names of those who suffered before you. The other lads, hardened by Midlands streets, divide into predators and prey, their eyes sizing you up. Your Yemeni heritage and Birmingham roots make you a target. A boy sneers, “What are you, some Arab?” You mutter “Greek,” but your thick Brummie accent betrays you. Your grandmother, who raised you with your mother above a Smethwick off-licence, named you Michael instead of Mohammed—a fragile shield in 1970s Britain’s racist undercurrent. The judge called you a “product of a broken home,” wild and uncontrollable, sentencing you to be shattered here.

Devaney’s Reign of Terror

The gym is Eastwood Park’s chamber of horror, ruled by Patrick Devaney, a wiry figure with a ginger beard and a smirk that cuts like glass. They call him “The Ginger Bully.” He wields a rubber hose dubbed “Mabel” and a sharpened metal ruler, tools to carve fear into flesh. During morning inspections, he stalks the line, eyes hunting for imperfections—dirty nails, slouched shoulders, a frayed uniform. One sweltering morning, he spots a speck under your nail. His ruler flashes down, splitting your knuckle. Pain explodes, blood pooling on the concrete. “Cleanliness is discipline, you filthy half-breed,” he spits, his voice a blade. You meet his gaze, jaw clenched, refusing to scream, though your hands tremble as you scrub them raw that night, soap stinging like betrayal. Survivors later call Devaney a predator, drunk on control, forcing boys into bare-knuckle fights or brutal exercises—bunny hops, wall sits, sprints until your legs give out. His racist taunts wound deeper than his blows, targeting you and other boys of colour. At night, boozy watchmen drag you from your cell, forcing you to bunny-hop corridors while they jeer. Men in their 40s make lads like Derek and Winston hold the “Starfish” pose against walls until their bodies quake, humiliation their sport.

A Mother’s Visit and Devaney’s Retribution

One grey afternoon, your mum visits, her eyes heavy with worry. In a quiet corner, you pour out your pain—how Devaney’s cruelty grinds you down, his slurs and blows a daily torment. “He’s a monster, Mum,” you whisper, voice cracking. “He enjoys it.” You don’t know Devaney’s lurking nearby, his ears catching every word. Later, in the gym, his smirk twists into something uglier. “Heard you crying to your mummy, Michael,” he sneers, mimicking your Brummie accent with cruel exaggeration. “Thanks to you, lads, you’re all doing extra circuits today!” He barks orders for relentless sprints and burpees, his eyes locked on you. The other boys, drenched in sweat and fury, turn on you. “Why’d you open your mouth, you idiot?” one hisses. Their glares burn; you feel small, belittled, humiliated. The extra circuits leave your legs shaking, and the lads’ anger follows you to the dorm, their muttered threats and shoves piling aggravation onto your already heavy day. Devaney’s punishment isn’t just physical—it’s a calculated strike to isolate you, to make you the scapegoat.

Brutal Gym Sessions

Gym sessions are a gauntlet of pain and shame. Devaney’s drills push you past breaking: push-ups until your arms collapse, sprints until your lungs burn acid, medicine balls heaved until your shoulders scream. You’re small but quick, weaving through burpees and circuits, earning grudging nods from other boys. But Devaney thrives on your suffering. One humid afternoon, he pairs you with a towering 17-year-old, fists like concrete, desperate to prove himself. His punches slam into you—your lip splits, ribs bruise, blood sharp on your tongue. You stagger to your dorm, collapsing on the mattress, whispering to yourself: I’ll outlast this. Dev’s slurs—“You’ll never belong”—echo the hate you’ve faced on Birmingham’s streets, cutting scars no fist could match.

Moments of Resistance

You fight back in small, fierce ways. In the kitchen, peeling onions or scrubbing pots under officers’ paddle swings, you connect with Harry, a ginger-haired car thief from Manchester who dreams of fronting a punk band. Late-night whispers about music, girls, and freedom become your oxygen. Harry smuggles a spliff rolled in Bible paper; you share it in the dark, its faint glow a middle finger to the screws. Winston, a quiet Jamaican boy, teaches you to hum reggae, the melodies muffling screams during murderball—a vicious game where Devaney pits white boys against Black and Asian lads, fanning racial hate for his amusement. These acts—a shared smoke, a hummed tune, a glance of solidarity—keep your soul from breaking.

Lasting Scars

Your ribs heal, your knuckles scab, but the fear festers like rot. Devaney’s taunts and blows breed a dread that chokes you: the next inspection, the next strike, the screams slicing through suffocating nights. Nightmares of his shadow and slurs tangle with memories of your father’s silent shame and your mother’s courtroom tears. Escape is a cruel dream—barbed wire and walls laugh at the thought. You carve tally marks behind your bed, each a silent vow to endure. The “short, sharp shock” doesn’t reform you; it teaches you to bury pain, sharpen your instincts, and distrust power.

Autumn 1981: A Fragile Freedom

On a crisp September morning in 1981 you walk out of Eastwood Park, clutching a plastic bag with a worn jumper, a toothbrush, and your mum’s crumpled letter. Birmingham’s streets roar with life, their freedom jarring after three months of captivity. You flinch at loud voices, bracing at sudden moves, a quiet rage simmering beneath your defiance. Your mother’s hug anchors you, but Devaney’s ruler and the gym’s brutality linger like ghosts. You vow to rebuild, to prove Eastwood hasn’t won, though its scars—seen and unseen—will shape you for decades.

2023: A Reckoning

In 2023, at 59, a Birmingham Mail article (17 Jan 2025) tears open old wounds. Patrick Devaney, now frail and grey, is convicted of misconduct in public office, sentenced to three-and-a-half years after twenty-two survivors expose his sadistic reign at Eastwood Park. The punishment feels like a slap for the pain he inflicted on over 100 boys. The article details the Eastwood Park Detention Centre Settlement Scheme, launched by the Ministry of Justice to compensate survivors of physical and sexual abuse with £3,000 to £9,500 and an apology letter, no legal costs required (Birmingham Mail, 17 Jan 2025). Jane Matthews of Jordans Solicitors says, “Acknowledging the abuse is a vital step toward closure for survivors” (Birmingham Mail, 17 Jan 2025). Relief mixes with rage—justice, decades late, feels hollow. Call Jordans Solicitors at 033 0300 1103 to join the scheme, closing in January 2026, to loosen Eastwood’s grip.

Michael’s Life Today

Nearing 60, you burn with life. You chase summers in Ibiza’s pulsing clubs, winters in India’s vibrant markets, and roam Europe’s bustling streets. Your Birmingham home hums with laughter, shared with a girlfriend who doesn’t know your past. A fitness fanatic, you train five days a week, perhaps defying Eastwood’s brutal drills. Yet its shadow lingers—a tightness in your chest at raised voices, nightmares of tally marks and Devaney’s sneer. The settlement scheme offers a chance to voice your truth and reclaim a piece of yourself. Your Birmingham grit and Yemeni fire push you forward, unbroken.

A Call to Action

If you or someone you know endured abuse at Eastwood Park Detention Centre between 1970 and 1983, your story matters. Contact Jordans Solicitors at 033 0300 1103 to explore the Eastwood Park Detention Centre Settlement Scheme, closing in January 2026. The Ministry of Justice handles claims with care, ensuring justice for survivors (Birmingham Mail, 17 Jan 2025). Report to Avon and Somerset Police on 101 or online. Visit www.tommykennedyiv.com to share your experience and demand accountability. The process may be heavy, so lean on friends, family, or Samaritans (116 123, www.samaritans.org) for support.

July 1, 2025

EASTWOOD PARK