Blood on the Blocks: When the Guards Walked Out

Lest We Forget – The 1997 Prison Riots in Jamaica

It’s 2025. Twenty-eight years have passed, but I still recall the stories about August 1997 like it was yesterday. Between the 19th and 22nd, Jamaica’s prisons became killing fields. Warders at St Catherine District Prison in Spanish Town and Kingston’s infamous General Penitentiary walked off the job. Not over wages, not over food, not over conditions — they walked because of condoms.

The government had announced a plan to issue condoms to both guards and inmates to slow the spread of HIV. Practical. Life-saving. But in a country where homosexuality was criminalised and violently stigmatised, the warders saw it as an insult — a mark against their manhood. They left the gates wide open.

And what followed was carnage.

The Killings

With no authority to keep order, the strongest seized control. Old grudges were settled. Political loyalties became death sentences. And the weakest — men accused of being homosexual — were the first to die.

Officially, at least sixteen inmates were killed. Survivors insist the number was higher — twenty-seven, some say more. Henzel Muir, who lived through it, told the Jamaica Observer:

“The weakest prisoners, the ones accused of being homosexual, were the first to die.”

(Jamaica Observer)

He described the screams echoing through the blocks, men dragged from their cells, and knives cutting down anyone in the way.

Once the purge of suspected homosexuals ended, the violence turned political. Jamaica’s prisons have always mirrored street politics — party loyalties matter, even inside. In those four days, politics became another weapon.

Headlines Without Truth

The international press covered it briefly. The New York Times ran the story under the flat headline: “Jamaica Tries to Quiet 2 Prisons After Riots” (NYT, 25 August 1997). Sixteen dead, dozens injured, order restored.

But numbers and statements never tell the full story. The chaos, the fear, the prejudice turned permission — none of that appeared in official reports. Families were left with questions and no answers. Commissions promised reform but delivered little.

Condoms, Stigma, and Silence

It’s important to remember why it happened. The HIV epidemic inside Jamaica’s prisons was no secret. The government’s plan to hand out condoms was practical, meant to save lives. But stigma was stronger than reason. To the warders, condoms equalled homosexuality, and in a society that criminalised it, that was enough to spark a mass walkout.

The vacuum they left was filled with chaos and death.

Timeline: 19–22 August 1997

19 August: Warders begin mass sick-out. Prisons left unguarded. First skirmishes reported.

20 August: Violence escalates. Weakest inmates, especially those suspected of homosexuality, are dragged from cells and killed. Political rivalries spark targeted attacks.

21 August: Riots peak. Blocks are overtaken by gangs. Screams echo through the corridors. Official reports still minimal.

22 August: External forces regain partial control. Death toll officially recorded as sixteen, though survivors claim higher. Commissions promised, but little real accountability.

Twenty-Eight Years On

Now in 2025, the riots have mostly faded from memory. Survivors carry the scars. Families still wonder why their sons, brothers, and fathers never returned. Society looks away, the story buried under decades of silence.

And that silence is dangerous. When authority collapses, the weak pay first. In 1997, men already condemned by society — homosexuals, politically marked, powerless — were condemned again, this time to die in darkness.

Lest We Forget

Sixteen dead, the official line says. Twenty-seven, the survivors claim. Maybe more. Numbers don’t matter as much as the truth: lives were thrown away because stigma opened the door.

When the guards walked out, death walked in.

We owe it to the men who never stood a chance to speak their names, even if the world forgets.

Lest we forget.

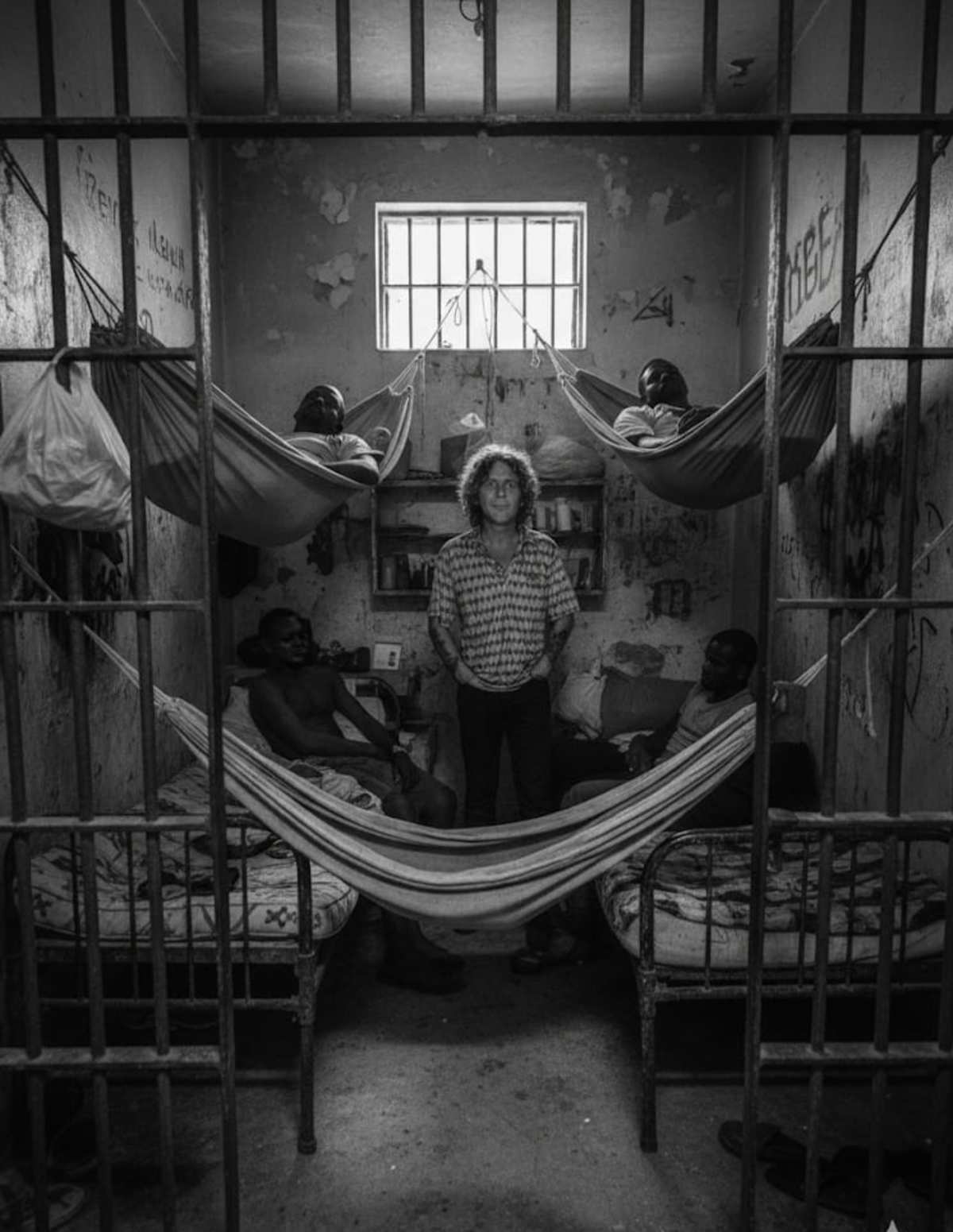

Author’s Note

I write this not from outside looking in, but as someone who’s lived behind those walls. I know the weight of fear, the slam of iron gates, the way order can vanish in a heartbeat. In prison, your life can hang on who you share a cell with, which gang claims your block, or how the guards choose to act.

In August 1997, when the warders walked out, that choice vanished. Men who were already at the bottom paid with their lives.

To forget them is to bury them twice.

— Tommy Kennedy IV

Author of Nightmare in Jamaica

September 30, 2025

KILLING FIELDS